Lucky Break

How I became a writer

A fiction writer is a person who invents stories.

But how does one start out on a job like this? How does one become a full-time professional fiction writer?

Charles Dickens found it easy. At the age of twenty-four, he simply sat down and wrote Pickwick Papers, which became an immediate best-seller. But Dickens was a genius, and geniuses are different from the rest of us.

In this century (it was not always so in the last one), just about every single writer who has finally become successful in the world of fiction has started out in some other job – a schoolteacher, perhaps, or a doctor or a journalist or a lawyer. (Alice in Wonderland was written by a mathematician, and The Wind in the Willows by a civil servant.) The first attempts at writing have therefore always had to be done in spare time, usually at night.

The reason for this is obvious. When you are adult, it is necessary to earn a living. To earn a living, you must get a job. You must if possible get a job that guarantees you so much money a week. But however much you may want to take up fiction writing as a career, it would be pointless to go along to a publisher and say, ‘I want a job as a fiction writer.’ If you did that, he would tell you to buzz off and write the book first. And even if you brought a finished book to him and he liked it well enough to publish it, he still wouldn’t give you a job. He would give you an advance of perhaps five hundred pounds, which he would get back again later by deducting it from your royalties. (A royalty, by the way, is the money that a writer gets from the publisher for each copy of his book that is sold. The average royalty a writer gets is ten per cent of the price of the book itself in the book shop. Thus, for a book selling at four pounds, the writer would get forty pence. For a paperback selling at fifty pence, he would get five pence.)

It is very common for a hopeful fiction writer to spend two years of his spare time writing a book which no publisher will publish. For that he gets nothing at all except a sense of frustration.

If he is fortunate enough to have a book accepted by a publisher, the odds are that as a first novel it will in the end sell only about three thousand copies. That will earn him maybe a thousand pounds. Most novels take at least one year to write, and one thousand pounds a year is not enough to live on these days. So you can see why a budding fiction writer invariably has to start out in another job first of all. If he doesn’t, he will almost certainly starve.

Here are some of the qualities you should possess or should try to acquire if you wish to become a fiction writer:

- You should have a lively imagination.

- You should be able to write well. By that I mean you should be able to make a scene come alive in the reader’s mind. Not everybody has this ability. It is a gift, and you either have it or you don’t.

- You must have stamina. In other words, you must be able to stick to what you are doing and never give up, for hour after hour, day after day, week after week and month after month.

- You must be a perfectionist. That means you must never be satisfied with what you have written until you have rewritten it again and again, making it as good as you possibly can.

- You must have strong self-discipline. You are working alone. No one is employing you. No one is around to give you the sack if you don’t turn up for work, or to tick you off if you start slacking.

- It helps a lot if you have a keen sense of humour. This is not essential when writing for grown-ups, but for children, it’s vital.

- You must have a degree of humility. The writer who thinks that his work is marvellous is heading for trouble.

Let me tell you how I myself slid in through the back door and found myself in the world of fiction.

At the age of eight, in 1924, I was sent away to boarding-school in a town called Weston-super-Mare, on the south-west coast of England. Those were days of horror, of fierce discipline, of no talking in the dormitories, no running in the corridors, no untidiness of any sort, no this or that or the other, just rules and still more rules that had to be obeyed. And the fear of the dreaded cane hung over us like the fear of death all the time.

‘The headmaster wants to see you in his study.’ Words of doom. They sent shivers over the skin of your stomach. But off you went, aged perhaps nine years old, down the long bleak corridors and through an archway that took you into the headmaster’s private area where only horrible things happened and the smell of pipe tobacco hung in the air like incense. You stood outside the awful black door, not daring even to knock. You took deep breaths. If only your mother were here, you told yourself, she would not let this happen. She wasn’t here. You were alone. You lifted a hand and knocked softly, once.

‘Come in! Ah yes, it’s Dahl. Well, Dahl, it’s been reported to me that you were talking during prep last night.’

‘Please, sir, I broke my nib and I was only asking Jenkins if he had another one to lend me.’

‘I will not tolerate talking in prep. You know that very well.’

Already this giant of a man was crossing to the tall corner cupboard and reaching up to the top of it where he kept his canes.

‘Boys who break rules have to be punished.’

‘Sir … I … I had a bust nib … I …’

‘That is no excuse. I am going to teach you that it does not pay to talk during prep.’

He took a cane down that was about three feet long with a little curved handle at one end. It was thin and white and very whippy. ‘Bend over and touch your toes. Over there by the window.’

‘But, sir …’

‘Don’t argue with me, boy. Do as you’re told.’

I bent over. Then I waited. He always kept you waiting for about ten seconds, and that was when your knees began to shake.

‘Bend lower, boy! Touch your toes!’

I stared at the toecaps of my black shoes and I told myself that any moment now this man was going to bash the cane into me so hard that the whole of my bottom would change colour. The welts were always very long, stretching right across both buttocks, blue-black with brilliant scarlet edges, and when you ran your fingers over them ever so gently afterwards, you could feel the corrugations.

Swish! … Crack!

Then came the pain. It was unbelievable, unbearable, excruciating. It was as though someone had laid a white-hot poker across your backside and pressed hard.

The second stroke would be coming soon and it was as much as you could do to stop putting your hands in the way to ward it off. It was the instinctive reaction. But if you did that, it would break your fingers.

Swish! … Crack!

The second one landed right alongside the first and the white-hot poker was pressing deeper and deeper into the skin.

Swish! … Crack!

The third stroke was where the pain always reached its peak. It could go no further. There was no way it could get any worse. Any more strokes after that simply prolonged the agony. You tried not to cry out. Sometimes you couldn’t help it. But whether you were able to remain silent or not, it was impossible to stop the tears. They poured down your cheeks in streams and dripped on to the carpet.

The important thing was never to flinch upwards or straighten up when you were hit. If you did that, you got an extra one.

Slowly, deliberately, taking plenty of time, the headmaster delivered three more strokes, making six in all.

‘You may go.’ The voice came from a cavern miles away, and you straightened up slowly, agonizingly, and grabbed hold of your burning buttocks with both hands and held them as tight as you could and hopped out of the room on the very tips of your toes.

That cruel cane ruled our lives. We were caned for talking in the dormitory after lights out, for talking in class, for bad work, for carving our initials on the desk, for climbing over walls, for slovenly appearance, for flicking paper-clips, for forgetting to change into house-shoes in the evenings, for not hanging up our games clothes, and above all for giving the slightest offence to any master. (They weren’t called teachers in those days.) In other words, we were caned for doing everything that it was natural for small boys to do.

So we watched our words. And we watched our steps. My goodness, how we watched our steps. We became incredibly alert. Wherever we went, we walked carefully, with ears pricked for danger, like wild animals stepping softly through the woods.

Apart from the masters, there was another man in the school who frightened us considerably. This was Mr Pople. Mr Pople was a paunchy, crimson-faced individual who acted as school-porter, boiler superintendent and general handyman. His power stemmed from the fact that he could (and he most certainly did) report us to the headmaster upon the slightest provocation. Mr Pople’s moment of glory came each morning at seven-thirty precisely, when he would stand at the end of the long main corridor and ‘ring the bell’. The bell was huge and made of brass, with a thick wooden handle, and Mr Pople would swing it back and forth at arm’s length in a special way of his own, so that it went clangetty-clang-clang, clangetty-clang-clang, clangetty-clang-clang. At the sound of the bell, all the boys in the school, one hundred and eighty of us, would move smartly to our positions in the corridor. We lined up against the walls on both sides and stood stiffly to attention, awaiting the headmaster’s inspection.

But at least ten minutes would elapse before the headmaster arrived on the scene, and during this time, Mr Pople would conduct a ceremony so extraordinary that to this day I find it hard to believe it ever took place. There were six lavatories in the school, numbered on their doors from one to six. Mr Pople, standing at the end of the long corridor, would have in the palm of his hand six small brass discs, each with a number on it, one to six. There was absolute silence as he allowed his eye to travel down the two lines of stiffly-standing boys. Then he would bark out a name, ‘Arkle!’

Arkle would fall out and step briskly down the corridor to where Mr Pople stood. Mr Pople would hand him a brass disc. Arkle would then march away towards the lavatories, and to reach them he would have to walk the entire length of the corridor, past all the stationary boys, and then turn left. As soon as he was out of sight, he was allowed to look at his disc and see which lavatory number he had been given.

‘Highton!’ barked Mr Pople, and now Highton would fall out to receive his disc and march away.

‘Angel!’ …

‘Williamson!’ …

‘Gaunt!’ …

‘Price!’ …

In this manner, six boys selected at Mr Pople’s whim were dispatched to the lavatories to do their duty. Nobody asked them if they might or might not be ready to move their bowels at seven-thirty in the morning before breakfast. They were simply ordered to do so. But we considered it a great privilege to be chosen because it meant that during the headmaster’s inspection we would be sitting safely out of reach in blessed privacy.

In due course, the headmaster would emerge from his private quarters and take over from Mr Pople. He walked slowly down one side of the corridor, inspecting each boy with the utmost care, strapping his wristwatch on to his wrist as he went along. The morning inspection was an unnerving experience. Every one of us was terrified of the two sharp brown eyes under their bushy eyebrows as they travelled slowly up and down the length of one’s body.

‘Go away and brush your hair properly. And don’t let it happen again or you’ll be sorry.’

‘Let me see your hands. You have ink on them. Why didn’t you wash it off last night?’

‘Your tie is crooked, boy. Fall out and tie it again. And do it properly this time.’

‘I can see mud on that shoe. Didn’t I have to talk to you about that last week? Come and see me in my study after breakfast.’

And so it went on, the ghastly early-morning inspection. And by the end of it all, when the headmaster had gone away and Mr Pople started marching us into the dining-room by forms, many of us had lost our appetites for the lumpy porridge that was to come.

I have still got all my school reports from those days more than fifty years ago, and I’ve gone through them one by one, trying to discover a hint of promise for a future fiction writer. The subject to look at was obviously English Composition. But all my prep-school reports under this heading were flat and non-committal, excepting one. The one that took my eye was dated Christmas Term, 1928. I was then twelve, and my English teacher was Mr Victor Corrado. I remember him vividly, a tall, handsome athlete with black wavy hair and a Roman nose (who one night later on eloped with the matron, Miss Davis, and we never saw either of them again). Anyway, it so happened that Mr Corrado took us in boxing as well as in English Composition, and in this particular report it said under English, ‘See his report on boxing. Precisely the same remarks apply.’ So we look under Boxing, and there it says, ‘Too slow and ponderous. His punches are not well-timed and are easily seen coming.’

But just once a week at this school, every Saturday morning, every beautiful and blessed Saturday morning, all the shivering horrors would disappear and for two glorious hours I would experience something that came very close to ecstasy.

Unfortunately, this did not happen until one was ten years old. But no matter. Let me try to tell you what it was.

At exactly ten-thirty on Saturday mornings, Mr Pople’s infernal bell would go clangetty-clang-clang. This was a signal for the following to take place:

First, all boys of nine and under (about seventy all told) would proceed at once to the large outdoor asphalt playground behind the main building. Standing on the playground with legs apart and arms folded across her mountainous bosom was Miss Davis, the matron. If it was raining, the boys were expected to arrive in raincoats. If snowing or blowing a blizzard, then it was coats and scarves. And school caps, of course – grey with a red badge on the front – had always to be worn. But no Act of God, neither tornado nor hurricane nor volcanic eruption was ever allowed to stop those ghastly two-hour Saturday morning walks that the seven-, eight- and nine-year-old little boys had to take along the windy esplanades of Weston-super-Mare on Saturday mornings. They walked in crocodile formation, two by two, with Miss Davis striding alongside in tweed skirt and woollen stockings and a felt hat that must surely have been nibbled by rats.

The other thing that happened when Mr Pople’s bell rang out on Saturday mornings was that the rest of the boys, all those of ten and over (about one hundred all told) would go immediately to the main Assembly Hall and sit down. A junior master called S. K. Jopp would then poke his head around the door and shout at us with such ferocity that specks of spit would fly from his mouth like bullets and splash against the window panes across the room. ‘All right!’ he shouted. ‘No talking! No moving! Eyes front and hands on desks!’ Then out he would pop again.

We sat still and waited. We were waiting for the lovely time we knew would be coming soon. Outside in the driveway we heard the motor-cars being started up. All were ancient. All had to be cranked by hand. (The year, don’t forget, was around 1927/28.) This was a Saturday morning ritual. There were five cars in all, and into them would pile the entire staff of fourteen masters, including not only the headmaster himself but also the purple-faced Mr Pople. Then off they would roar in a cloud of blue smoke and come to rest outside a pub called, if I remember rightly, ‘The Bewhiskered Earl’. There they would remain until just before lunch, drinking pint after pint of strong brown ale. And two and a half hours later, at one o’clock, we would watch them coming back, walking very carefully into the dining-room for lunch, holding on to things as they went.

So much for the masters. But what of us, the great mass of ten-, eleven- and twelve-year-olds left sitting in the Assembly Hall in a school that was suddenly without a single adult in the entire place? We knew, of course, exactly what was going to happen next. Within a minute of the departure of the masters, we would hear the front door opening, and footsteps outside, and then, with a flurry of loose clothes and jangling bracelets and flying hair, a woman would burst into the room shouting, ‘Hello, everybody! Cheer up! This isn’t a burial service!’ or words to that effect. And this was Mrs O’Connor.

Blessed beautiful Mrs O’Connor with her whacky clothes and her grey hair flying in all directions. She was about fifty years old, with a horsey face and long yellow teeth, but to us she was beautiful. She was not on the staff. She was hired from somewhere in the town to come up on Saturday mornings and be a sort of baby-sitter, to keep us quiet for two and a half hours while the masters went off boozing at the pub.

But Mrs O’Connor was no baby-sitter. She was nothing less than a great and gifted teacher, a scholar and a lover of English Literature. Each of us was with her every Saturday morning for three years (from the age of ten until we left the school) and during that time we spanned the entire history of English Literature from A.D. 597 to the early nineteenth century.

Newcomers to the class were given for keeps a slim blue book called simply The Chronological Table, and it contained only six pages. Those six pages were filled with a very long list in chronological order of all the great and not so great landmarks in English Literature, together with their dates. Exactly one hundred of these were chosen by Mrs O’Connor and we marked them in our books and learned them by heart. Here are a few that I still remember:

| A.D. 597 | St Augustine lands in Thanet and brings Christianity to Britain | |

| 731 | Bede’s Ecclesiastical History | |

| 1215 | Signing of the Magna Carta | |

| 1399 | Langland’s Vision of Piers Plowman | |

| 1476 | Caxton sets up first printing press at Westminster | |

| 1478 | Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales | |

| 1485 | Malory’s Morte d’Arthur | |

| 1590 | Spenser’s Faërie Queene | |

| 1623 | First Folio of Shakespeare | |

| 1667 | Milton’s Paradise Lost | |

| 1668 | Dryden’s Essays | |

| 1678 | Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress | |

| 1711 | Addison’s Spectator | |

| 1719 | Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe | |

| 1726 | Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels | |

| 1733 | Pope’s Essay on Man | |

| 1755 | Johnson’s Dictionary | |

| 1791 | Boswell’s Life of Johnson | |

| 1833 | Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus | |

| 1859 | Darwin’s Origin of Species |

Mrs O’Connor would then take each item in turn and spend one entire Saturday morning of two and a half hours talking to us about it. Thus, at the end of three years, with approximately thirty-six Saturdays in each school year, she would have covered the one hundred items.

And what marvellous exciting fun it was! She had the great teacher’s knack of making everything she spoke about come alive to us in that room. In two and a half hours, we grew to love Langland and his Piers Plowman. The next Saturday, it was Chaucer, and we loved him, too. Even rather difficult fellows like Milton and Dryden and Pope all became thrilling when Mrs O’Connor told us about their lives and read parts of their work to us aloud. And the result of all this, for me at any rate, was that by the age of thirteen I had become intensely aware of the vast heritage of literature that had been built up in England over the centuries. I also became an avid and insatiable reader of good writing.

Dear lovely Mrs O’Connor! Perhaps it was worth going to that awful school simply to experience the joy of her Saturday mornings.

At thirteen I left prep school and was sent, again as a boarder, to one of our famous British public schools. They are not, of course, public at all. They are extremely private and expensive. Mine was called Repton, in Derbyshire, and our headmaster at the time was the Reverend Geoffrey Fisher, who later became Bishop of Chester, then Bishop of London, and finally Archbishop of Canterbury. In his last job, he crowned Queen Elizabeth II in Westminster Abbey.

The clothes we had to wear at this school made us look like assistants in a funeral parlour. The jacket was black, with a cutaway front and long tails hanging down behind that came below the backs of the knees. The trousers were black with thin grey stripes. The shoes were black. There was a black waistcoat with eleven buttons to do up every morning. The tie was black. Then there was a stiff starched white butterfly collar and a white shirt.

To top it all off, the final ludicrous touch was a straw hat that had to be worn at all times out of doors except when playing games. And because the hats got soggy in the rain, we carried umbrellas for bad weather.

You can imagine what I felt like in this fancy dress when my mother took me, at the age of thirteen, to the train in London at the beginning of my first term. She kissed me good-bye and off I went.

I naturally hoped that my long-suffering backside would be given a rest at my new and more adult school, but it was not to be. The beatings at Repton were more fierce and more frequent than anything I had yet experienced. And do not think for one moment that the future Archbishop of Canterbury objected to these squalid exercises. He rolled up his sleeves and joined in with gusto. His were the bad ones, the really terrifying occasions. Some of the beatings administered by this Man of God, this future Head of the Church of England, were very brutal. To my certain knowledge he once had to produce a basin of water, a sponge and a towel so that the victim could wash the blood away afterwards.

No joke, that.

Shades of the Spanish Inquisition.

But nastiest of all, I think, was the fact that prefects were allowed to beat their fellow pupils. This was a daily occurrence. The big boys (aged 17 or 18) would flog the smaller boys (aged 13, 14, 15) in a sadistic ceremony that took place at night after you had gone up to the dormitory and got into your pyjamas.

‘You’re wanted down in the changing-room.’

With heavy hands, you would put on your dressing-gown and slippers. Then you would stumble downstairs and enter the large wooden-floored room where the games clothes were hanging up around the walls. A single bare electric bulb hung from the ceiling. A prefect, pompous but very dangerous, was waiting for you in the centre of the room. In his hands, he held a long cane, and he was usually flexing it back and forth as you came in.

‘I suppose you know why you’re here,’ he would say.

‘Well, I …’

‘For the second day running you have burnt my toast!’

Let me explain this ludicrous remark. You were this particular prefect’s fag. That meant you were his servant, and one of your many duties was to make toast for him every day at teatime. For this, you used a long three-pronged toasting fork, and you stuck the bread on the end of it and held it up before an open fire, first one side, then the other. But the only fire where toasting was allowed was in the library, and as teatime approached, there were never less than a dozen wretched fags all jostling for position in front of the tiny grate. I was no good at this. I usually held the bread too close and the toast got burnt. But as we were never allowed to ask for a second slice and start again, the only thing to do was to scrape the burnt bits off with a knife. You seldom got away with this. The prefects were expert at detecting scraped toast. You would see your own tormentor sitting up there at the top table, picking up his toast, turning it over, examining it closely as though it were a small and very valuable painting. Then he would frown and you knew you were for it.

So now it was night-time and you were down in the changing-room in your dressing-gown and pyjamas, and the one whose toast you had burnt was telling you about your crime.

‘I don’t like burnt toast.’

‘I held it too close. I’m sorry.’

‘Which do you want? Four with the dressing-gown on, or three with it off?’

‘Four with it on,’ I said.

It was traditional to ask this question. The victim was always given a choice. But my own dressing-gown was made of thick brown camel-hair, and there was never any question in my mind that this was the better choice. To be beaten in pyjamas only was a very painful experience, and your skin nearly always got broken. But my dressing-gown stopped that from happening. The prefect knew, of course, all about this, and therefore whenever you chose to take an extra stroke and kept the dressing-gown on, he beat you with every ounce of his strength. Sometimes he would take a little run, three or four neat steps on his toes, to gain momentum and thrust, but either way, it was a savage business.

In the old days, when a man was about to be hanged, a silence would fall upon the whole prison and the other prisoners would sit very quietly in their cells until the deed had been done. Much the same thing happened at school when a beating was taking place. Upstairs in the dormitories, the boys would sit in silence on their beds in sympathy for the victim, and through the silence, from down below in the changing-room, would come the crack of each stroke as it was delivered.

My end-of-term reports from this school are of some interest. Here are just four of them, copied out word for word from the original documents:

Summer Term, 1930 (aged 14). English Composition. ‘I have never met a boy who so persistently writes the exact opposite of what he means. He seems incapable of marshalling his thoughts on paper.’

Easter Term, 1931 (aged 15). English Composition. ‘A persistent muddler. Vocabulary negligible, sentences malconstructed. He reminds me of a camel.’

Summer Term, 1932 (aged 16). English Composition. ‘This boy is an indolent and illiterate member of the class.’

Autumn Term, 1932 (aged 17). English Composition. ‘Consistently idle. Ideas limited.’ (And underneath this one, the future Archbishop of Canterbury had written in red ink, ‘He must correct the blemishes on this sheet.’)

Little wonder that it never entered my head to become a writer in those days.

When I left school at the age of eighteen, in 1934, I turned down my mother’s offer (my father died when I was three) to go to university. Unless one was going to become a doctor, a lawyer, a scientist, an engineer or some other kind of professional person, I saw little point in wasting three or four years at Oxford or Cambridge, and I still hold this view. Instead, I had a passionate wish to go abroad, to travel, to see distant lands. There were almost no commercial aeroplanes in those days, and a journey to Africa or the Far East took several weeks.

So I got a job with what was called the Eastern Staff of the Shell Oil Company, where they promised me that after two or three years’ training in England, I would be sent off to a foreign country.

‘Which one?’ I asked.

‘Who knows?’ the man answered. ‘It depends where there is a vacancy when you reach the top of the list. It could be Egypt or China or India or almost anywhere in the world.’

That sounded like fun. It was. When my turn came to be posted abroad three years later, I was told it would be East Africa. Tropical suits were ordered and my mother helped me pack my trunk. My tour of duty was for three years in Africa, then I would be allowed home on leave for six months. I was now twenty-one years old and setting out for faraway places. I felt great. I boarded the ship at London Docks and off she sailed.

That journey took two and a half weeks. We went through the Bay of Biscay and called in at Gibraltar. We headed down the Mediterranean by way of Malta, Naples and Port Said. We went through the Suez Canal and down the Red Sea, stopping at Port Sudan, then Aden. It was tremendously exciting. For the first time, I saw great sandy deserts, and Arab soldiers mounted on camels, and palm trees with dates growing on them, and flying fish and thousands of other marvellous things. Finally we reached Mombasa, in Kenya.

At Mombasa, a man from the Shell Company came on board and told me I must transfer to a small coastal vessel and go on to Dar-es-Salaam, the capital of Tanganyika (now Tanzania). And so to Dar-es-Salaam I went, stopping at Zanzibar on the way.

For the next two years, I worked for Shell in Tanzania, with my headquarters in Dar-es-Salaam. It was a fantastic life. The heat was intense but who cared? Our dress was khaki shorts, an open shirt and a topee on the head. I learned to speak Swahili. I drove up-country visiting diamond mines, sisal plantations, gold mines and all the rest of it.

There were giraffes, elephants, zebras, lions and antelopes all over the place, and snakes as well, including the Black Mamba which is the only snake in the world that will chase after you if it sees you. And if it catches you and bites you, you had better start saying your prayers. I learned to shake my mosquito boots upside down before putting them on in case there was a scorpion inside, and like everyone else, I got malaria and lay for three days with a temperature of one hundred and five point five.

In September 1939, it became obvious that there was going to be a war with Hitler’s Germany. Tanganyika, which only twenty years before had been called German East Africa, was still full of Germans. They were everywhere. They owned shops and mines and plantations all over the country. The moment war broke out, they would have to be rounded up. But we had no army to speak of in Tanganyika, only a few native soldiers, known as Askaris, and a handful of officers. So all of us civilian men were made Special Reservists. I was given an armband and put in charge of twenty Askaris. My little troop and I were ordered to block the road that led south out of Tanganyika into neutral Portuguese East Africa. This was an important job, for it was along that road most of the Germans would try to escape when war was declared.

I took my happy gang with their rifles and one machine-gun and set up a road-block in a place where the road passed through dense jungle, about ten miles outside the town. We had a field telephone to headquarters which would tell us at once when war was declared. We settled down to wait. For three days we waited. And during the nights, from all around us in the jungle, came the sound of native drums beating weird hypnotic rhythms. Once, I wandered into the jungle in the dark and came across about fifty natives squatting in a circle around a fire. One man only was beating the drum. Some were dancing round the fire. The remainder were drinking something out of coconut shells. They welcomed me into their circle. They were lovely people. I could talk to them in their language. They gave me a shell filled with a thick grey intoxicating fluid made of fermented maize. It was called, if I remember rightly, Pomba. I drank it. It was horrible.

The next afternoon, the field telephone rang and a voice said, ‘We are at war with Germany.’ Within minutes, far away in the distance, I saw a line of cars throwing up clouds of dust, heading our way, beating it for the neutral territory of Portuguese East Africa as fast as they could go.

Ho ho, I thought. We are going to have a little battle, and I called out to my twenty Askaris to prepare themselves. But there was no battle. The Germans, who were after all only civilian townspeople, saw our machine-gun and our rifles and quickly gave themselves up. Within an hour, we had a couple of hundred of them on our hands. I felt rather sorry for them. Many I knew personally, like Willy Hink the watchmaker and Herman Schneider who owned the soda-water factory. Their only crime had been that they were German. But this was war, and in the cool of the evening, we marched them all back to Dar-es-Salaam where they were put into a huge camp surrounded by barbed wire.

The next day, I got into my old car and drove north, heading for Nairobi, in Kenya, to join the R.A.F. It was a rough trip and it took me four days. Bumpy jungle roads, wide rivers where the car had to be put on to a raft and pulled across by a ferryman hauling on a rope, long green snakes sliding across the road in front of the car. (N.B. Never try to run over a snake because it can be thrown up into the air and may land inside your open car. It’s happened many times.) I slept at night in the car. I passed below the beautiful Mount Kilimanjaro, which had a hat of snow on its head. I drove through the Masai country where the men drank cows’ blood and every one of them seemed to be seven feet tall. I nearly collided with a giraffe on the Serengeti Plain. But I came safely to Nairobi at last and reported to R.A.F. headquarters at the airport.

For six months, they trained us in small aeroplanes called Tiger Moths, and those days were also glorious. We skimmed all over Kenya in our little Tiger Moths. We saw great herds of elephants. We saw the pink flamingoes on Lake Nakuru. We saw everything there was to see in that magnificent country. And often, before we could take off, we had to chase the zebras off the flying-field. There were twenty of us training to be pilots out there in Nairobi. Seventeen of those twenty were killed during the war.

From Nairobi, they sent us up to Iraq, to a desolate airforce base near Baghdad to finish our training. The place was called Habbaniyih, and in the afternoons it got so hot (130 degrees in the shade) that we were not allowed out of our huts. We just lay on the bunks and sweated. The unlucky ones got heat-stroke and were taken to hospital and packed in ice for several days. This either killed them or saved them. It was a fifty-fifty chance.

At Habbaniyih, they taught us to fly more powerful aeroplanes with guns in them, and we practised shooting at drogues (targets in the air pulled behind other planes) and at objects on the ground.

Finally, our training was finished, and we were sent to Egypt to fight against the Italians in the Western Desert of Libya. I joined 80 Squadron, which flew fighters, and at first we had only ancient single-seater bi-planes called Gloster Gladiators. The two machine-guns on a Gladiator were mounted one on either side of the engine, and they fired their bullets, believe it or not, through the propeller. The guns were somehow synchronized with the propeller shaft so that in theory the bullets missed the whirling propeller blades. But as you might guess, this complicated mechanism often went wrong and the poor pilot, who was trying to shoot down the enemy, shot off his own propeller instead.

I myself was shot down in a Gladiator which crashed far out in the Libyan desert between the enemy lines. The plane burst into flames, but I managed to get out and was finally rescued and carried back to safety by our own soldiers who crawled out across the sand under cover of darkness.

That crash sent me to hospital in Alexandria for six months with a fractured skull and a lot of burns. When I came out, in April 1941, my squadron had been moved to Greece to fight the Germans who were invading from the north. I was given a Hurricane and told to fly it from Egypt to Greece and join the squadron. Now, a Hurricane fighter was not at all like the old Gladiator. It had eight Browning machine-guns, four in each wing, and all eight of them fired simultaneously when you pressed the small button on your joy-stick. It was a magnificent plane, but it had a range of only two hours’ flying-time. The journey to Greece, non-stop, would take nearly five hours, always over the water. They put extra fuel tanks on the wings. They said I would make it. In the end, I did. But only just. When you are six feet six inches tall, as I am, it is no joke to be sitting crunched up in a tiny cockpit for five hours.

In Greece, the R.A.F. had a total of about eighteen Hurricanes. The Germans had at least one thousand aeroplanes to operate with. We had a hard time. We were driven from our aerodrome outside Athens (Elevis), and flew for a while from a small secret landing strip further west (Menidi). The Germans soon found that one and bashed it to bits, so with the few planes we had left, we flew off to a tiny field (Argos) right down in the south of Greece, where we hid our Hurricanes under the olive trees when we weren’t flying.

But this couldn’t last long. Soon, we had only five Hurricanes left, and not many pilots still alive. Those five planes were flown to the island of Crete. The Germans captured Crete. Some of us escaped. I was one of the lucky ones. I finished up back in Egypt. The squadron was re-formed and re-equipped with Hurricanes. We were sent off to Haifa, which was then in Palestine (now Israel), where we fought the Germans again and the Vichy French in Lebanon and Syria.

At that point, my old head injuries caught up with me. Severe headaches compelled me to stop flying. I was invalided back to England and sailed on a troopship from Suez to Durban to Capetown to Lagos to Liverpool, chased by German submarines in the Atlantic and bombed by long-range Focke-Wulf aircraft every day for the last week of the voyage.

I had been away from home for four years. My mother, bombed out of her own house in Kent during the Battle of Britain and now living in a small thatched cottage in Buckinghamshire, was happy to see me. So were my four sisters and my brother. I was given a month’s leave. Then suddenly I was told I was being sent to Washington D.C. in the United States of America as Assistant Air Attaché. This was January 1942, and one month earlier the Japanese had bombed the American fleet in Pearl Harbor. So the United States was now in the war as well.

I was twenty-six years old when I arrived in Washington, and I still had no thoughts of becoming a writer.

During the morning of my third day, I was sitting in my new office at the British Embassy and wondering what on earth I was meant to be doing, when there was a knock on my door. ‘Come in.’

A very small man with thick steel-rimmed spectacles shuffled shyly into the room. ‘Forgive me for bothering you,’ he said.

‘You aren’t bothering me at all,’ I answered. ‘I’m not doing a thing.’

He stood before me looking very uncomfortable and out of place. I thought perhaps he was going to ask for a job.

‘My name,’ he said, ‘is Forester. C. S. Forester.’

I nearly fell out of my chair. ‘Are you joking?’ I said.

‘No,’ he said, smiling. ‘That’s me.’

And it was. It was the great writer himself, the inventor of Captain Hornblower and the best teller of tales about the sea since Joseph Conrad. I asked him to take a seat.

‘Look,’ he said. ‘I’m too old for the war. I live over here now. The only thing I can do to help is to write things about Britain for the American papers and magazines. We need all the help America can give us. A magazine called the Saturday Evening Post will publish any story I write. I have a contract with them. And I have come to you because I think you might have a good story to tell. I mean about flying.’

‘No more than thousands of others,’ I said. ‘There are lots of pilots who have shot down many more planes than me.’

‘That’s not the point,’ Forester said. ‘You are now in America, and because you have, as they say over here, “been in combat”, you are a rare bird on this side of the Atlantic. Don’t forget they have only just entered the war.’

‘What do you want me to do?’ I asked.

‘Come and have lunch with me,’ he said. ‘And while we’re eating, you can tell me all about it. Tell me your most exciting adventure and I’ll write it up for the Saturday Evening Post. Every little bit helps.’

I was thrilled. I had never met a famous writer before. I examined him closely as he sat in my office. What astonished me was that he looked so ordinary. There was nothing in the least unusual about him. His face, his conversation, his eyes behind the spectacles, even his clothes were all exceedingly normal. And yet here was a writer of stories who was famous the world over. His books had been read by millions of people. I expected sparks to be shooting out of his head, or at the very least, he should have been wearing a long green cloak and a floppy hat with a wide brim.

But no. And it was then I began to realize for the first time that there are two distinct sides to a writer of fiction. First, there is the side he displays to the public, that of an ordinary person like anyone else, a person who does ordinary things and speaks an ordinary language. Second, there is the secret side which comes out in him only after he has closed the door of his workroom and is completely alone. It is then that he slips into another world altogether, a world where his imagination takes over and he finds himself actually living in the places he is writing about at that moment. I myself, if you want to know, fall into a kind of trance and everything around me disappears. I see only the point of my pencil moving over the paper, and quite often two hours go by as though they were a couple of seconds.

‘Come along,’ C. S. Forester said to me. ‘Let’s go to lunch. You don’t seem to have anything else to do.’

As I walked out of the Embassy side by side with the great man, I was churning with excitement. I had read all the Hornblowers and just about everything else he had written. I had, and still have, a great love for books about the sea. I had read all of Conrad and all of that other splendid sea-writer, Captain Marryat (Mr Midshipman Easy, From Powder Monkey to Admiral, etc.), and now here I was about to have lunch with somebody who, to my mind, was also pretty terrific.

He took me to a small expensive French restaurant somewhere near the Mayflower Hotel in Washington. He ordered a sumptuous lunch, then he produced a notebook and a pencil (ballpoint pens had not been invented in 1942) and laid them on the tablecloth. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘tell me about the most exciting or frightening or dangerous thing that happened to you when you were flying fighter planes.’

I tried to get going. I started telling him about the time I was shot down in the Western Desert and the plane had burst into flames.

The waitress brought two plates of smoked salmon. While we tried to eat it, I was trying to talk and Forester was trying to take notes.

The main course was roast duck with vegetables and potatoes and a thick rich gravy. This was a dish that required one’s full attention as well as two hands. My narrative began to flounder. Forester kept putting down the pencil and picking up the fork, and vice versa. Things weren’t going well. And apart from that, I have never been much good at telling stories aloud.

‘Look,’ I said. ‘If you like, I’ll try to write down on paper what happened and send it to you. Then you can rewrite it properly yourself in your own time. Wouldn’t that be easier? I could do it tonight.’

That, though I didn’t know it at the time, was the moment that changed my life.

‘A splendid idea,’ Forester said. ‘Then I can put this silly notebook away and we can enjoy our lunch. Would you really mind doing that for me?’

‘I don’t mind a bit,’ I said. ‘But you mustn’t expect it to be any good. I’ll just put down the facts.’

‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘So long as the facts are there, I can write the story. But please,’ he added, ‘let me have plenty of detail. That’s what counts in our business, tiny little details, like you had a broken shoelace on your left shoe, or a fly settled on the rim of your glass at lunch, or the man you were talking to had a broken front tooth. Try to think back and remember everything.’

‘I’ll do my best,’ I said.

He gave me an address where I could send the story, and then we forgot all about it and finished our lunch at leisure. But Mr Forester was not a great talker. He certainly couldn’t talk as well as he wrote, and although he was kind and gentle, no sparks ever flew out of his head and I might just as well have been talking to an intelligent stockbroker or lawyer.

That night, in the small house I lived in alone in a suburb of Washington, I sat down and wrote my story. I started at about seven o’clock and finished at midnight. I remember I had a glass of Portuguese brandy to keep me going. For the first time in my life, I became totally absorbed in what I was doing. I floated back in time and once again I was in the sizzling hot desert of Libya, with white sand underfoot, climbing up into the cockpit of the old Gladiator, strapping myself in, adjusting my helmet, starting the motor and taxiing out for take-off. It was astonishing how everything came back to me with absolute clarity. Writing it down on paper was not difficult. The story seemed to be telling itself, and the hand that held the pencil moved rapidly back and forth across each page. Just for fun, when it was finished, I gave it a title. I called it ‘A Piece of Cake’.

The next day, somebody in the Embassy typed it out for me and I sent it off to Mr Forester. Then I forgot all about it.

Exactly two weeks later, I received a reply from the great man. It said:

Dear RD, You were meant to give me notes, not a finished story. I’m bowled over. Your piece is marvellous. It is the work of a gifted writer. I didn’t touch a word of it. I sent it at once under your name to my agent, Harold Matson, asking him to offer it to the Saturday Evening Post with my personal recommendation. You will be happy to hear that the Post accepted it immediately and have paid one thousand dollars. Mr Matson’s commission is ten per cent. I enclose his check for nine hundred dollars. It’s all yours. As you will see from Mr Matson’s letter, which I also enclose, the Post is asking if you will write more stories for them. I do hope you will. Did you know you were a writer? With my very best wishes and congratulations, C. S. Forester.

‘A Piece of Cake’ is printed at the end of this book.

Well! I thought. My goodness me! Nine hundred dollars! And they’re going to print it! But surely it can’t be as easy as all that?

Oddly enough, it was.

The next story I wrote was fiction. I made it up. Don’t ask me why. And Mr Matson sold that one, too. Out there in Washington in the evenings over the next two years, I wrote eleven short stories. All were sold to American magazines, and later they were published in a little book called Over to You.

Early on in this period, I also had a go at a story for children. It was called ‘The Gremlins’, and this I believe was the first time the word had been used. In my story, Gremlins were tiny men who lived on R.A.F. fighter-planes and bombers, and it was the Gremlins, not the enemy, who were responsible for all the bullet-holes and burning engines and crashes that took place during combat. The Gremlins had wives called Fifinellas, and children called Widgets, and although the story itself was clearly the work of an inexperienced writer, it was bought by Walt Disney who decided he was going to make it into a full-length animated film. But first it was published in Cosmopolitan Magazine with Disney’s coloured illustrations (December 1942), and from then on, news of the Gremlins spread rapidly through the whole of the R.A.F. and the United States Air Force, and they became something of a legend.

Because of the Gremlins, I was given three weeks’ leave from my duties at the Embassy in Washington and whisked out to Hollywood. There, I was put up at Disney’s expense in a luxurious Beverly Hills hotel and given a huge shiny car to drive about in. Each day, I worked with the great Disney at his studios in Burbank, roughing out the story-line for the forthcoming film. I had a ball. I was still only twenty-six. I attended story-conferences in Disney’s enormous office where every word spoken, every suggestion made, was taken down by a stenographer and typed out afterwards. I mooched around the rooms where the gifted and obstreperous animators worked, the men who had already created Snow White, Dumbo, Bambi and other marvellous films, and in those days, so long as these crazy artists did their work, Disney didn’t care when they turned up at the studio or how they behaved.

When my time was up, I went back to Washington and left them to it.

My Gremlin story was published as a children’s book in New York and London, full of Disney’s colour illustrations, and it was called of course The Gremlins. Copies are very scarce now and hard to come by. I myself have only one. The film, also, was never finished. I have a feeling that Disney was not really very comfortable with this particular fantasy. Out there in Hollywood, he was a long way away from the great war in the air that was going on in Europe. Furthermore, it was a story about the Royal Air Force and not about his own countrymen, and that, I think, added to his sense of bewilderment. So in the end, he lost interest and dropped the whole idea.

My little Gremlin book caused something else quite extraordinary to happen to me in those wartime Washington days. Eleanor Roosevelt read it to her grandchildren in the White House and was apparently much taken with it. I was invited to dinner with her and the President. I went, shaking with excitement. We had a splendid time and I was invited again. Then Mrs Roosevelt began asking me for week-ends to Hyde Park, the President’s country house. Up there, believe it or not, I spent a good deal of time alone with Franklin Roosevelt during his relaxing hours. I would sit with him while he mixed the martinis before Sunday lunch, and he would say things like, ‘I’ve just had an interesting cable from Mr Churchill.’ Then he would tell me what it said, something perhaps about new plans for the bombing of Germany or the sinking of U-Boats, and I would do my best to appear calm and chatty, though actually I was trembling at the realization that the most powerful man in the world was telling me these mighty secrets. Sometimes he drove me around the estate in his car, an old Ford I think it was, that had been specially adapted for his paralysed legs. It had no pedals. All the controls were worked by his hands. His secret-service men would lift him out of his wheel-chair into the driver’s seat, then he would wave them away and off we would go, driving at terrific speeds along the narrow roads.

One Sunday during lunch at Hyde Park, Franklin Roosevelt told a story that shook the assembled guests. There were about fourteen of us sitting on both sides of the long dining-room table, including Princess Martha of Norway and several members of the Cabinet. We were eating a rather insipid white fish covered with a thick grey sauce. Suddenly the President pointed a finger at me and said, ‘We have an Englishman here. Let me tell you what happened to another Englishman, a representative of the King, who was in Washington in the year 1827.’ He gave the man’s name, but I’ve forgotten it. Then he went on, ‘While he was over here, this fellow died, and the British for some reason insisted that his body be sent home to England for burial. Now the only way to do that in those days was to pickle it in alcohol. So the body was put into a barrel of rum. The barrel was lashed to the mast of a schooner and the ship sailed for home. After about four weeks at sea, the captain of the schooner noticed a most frightful stench coming from the barrel. And in the end, the smell became so appalling they had to cut the barrel loose and roll it overboard. But do you know why it stank so badly?’ the President asked, beaming at the guests with that famous wide smile of his. ‘I will tell you exactly why. Some of the sailors had drilled a hole in the bottom of the barrel and had inserted a bung. Then every night they had been helping themselves to the rum. And when they had drunk it all, that’s when the trouble started.’ Franklin Roosevelt let out a great roar of laughter. Several females at the table turned very pale and I saw them pushing their plates of boiled white fish gently away.

All the stories I wrote in those early days were fiction, except for that first one I did with C. S. Forester. Non-fiction, which means writing about things that have actually taken place, doesn’t interest me. I enjoy least of all writing about my own experiences. And that explains why this story is so lacking in detail. I could quite easily have described what it was like to be in a dog-fight with German fighters fifteen thousand feet above the Parthenon in Athens, or the thrill of chasing a Junkers 88 in and out the mountain peaks in Northern Greece, but I don’t want to do it. For me, the pleasure of writing comes with inventing stories.

Apart from the Forester story, I think I have only written one other non-fiction piece in my life, and I did this only because the subject was so enthralling I couldn’t resist it. The story is called ‘The Mildenhall Treasure’, and it’s in this book.

So there you are. That’s how I became a writer. Had I not been lucky enough to meet Mr Forester, it would probably never have happened.

Now, more than thirty years later, I’m still slogging away. To me, the most important and difficult thing about writing fiction is to find the plot. Good original plots are very hard to come by. You never know when a lovely idea is going to flit suddenly into your mind, but by golly, when it does come along, you grab it with both hands and hang on to it tight. The trick is to write it down at once, otherwise you’ll forget it. A good plot is like a dream. If you don’t write down your dream on paper the moment you wake up, the chances are you’ll forget it and it’ll be gone for ever.

So when an idea for a story comes popping into my mind, I rush for a pencil, a crayon, a lipstick, anything that will write, and scribble a few words that will later remind me of the idea. Often, one word is enough. I was once driving alone on a country road and an idea came for a story about someone getting stuck in an elevator between two floors in an empty house. I had nothing to write with in the car. So I stopped and got out. The back of the car was covered with dust. With one finger I wrote in the dust the single word ELEVATOR. That was enough. As soon as I got home, I went straight to my work-room and wrote the idea down in an old red-covered school exercise-book which is simply labelled ‘Short Stories’.

I have had this book ever since I started trying to write seriously. There are ninety-eight pages in the book. I’ve counted them. And just about every one of those pages is filled up on both sides with these so-called story ideas. Many are no good. But just about every story and every children’s book I have ever written has started out as a three- or four-line note in this little, much-worn red-covered volume. For example:

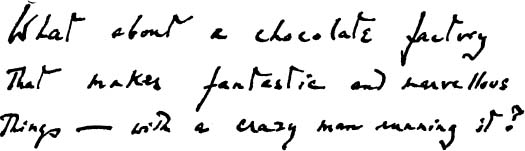

This became Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

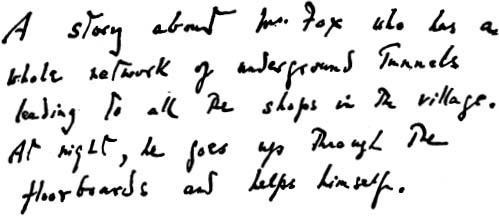

Fantastic Mr Fox.

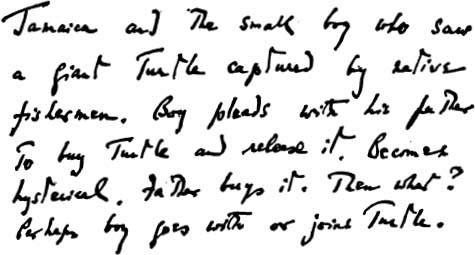

‘The Boy Who Talked with Animals.’

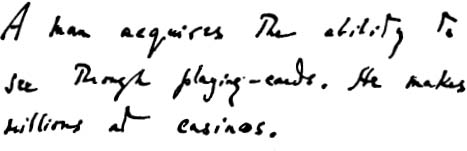

This became ‘Henry Sugar’.

Sometimes, these little scribbles will stay unused in the notebook for five or even ten years. But the promising ones are always used in the end. And if they show nothing else, they do, I think, demonstrate from what slender threads a children’s book or a short story must ultimately be woven. The story builds and expands while you are writing it. All the best stuff comes at the desk. But you can’t even start to write that story unless you have the beginnings of a plot. Without my little notebook, I would be quite helpless.